One of the chief reasons why our worldview is becoming so lopsided these days is that we have lost sight of the difference between the terms ‘civilization’ and ‘culture’. It’s a grand fallacy to think that these are the same, and, unfortunately, this is a mistake even the people in governance have been making since ever.

I see it this way — civilization is the body, whereas culture is its soul.

Over the millennia, people came and settled in places across the world and built villages and towns and cities and created the infrastructure they needed to live in—the buildings, the roads, the schools and hospitals—that is civilization.

And once the people settled, the essence that they collectively evolved as a common population—their art, their music, their languages, their cuisine and couture—that is culture.

Civilization is the visible part of human evolution, whereas culture is the invisible component. When you land into a new city, the first things you will see—their people, their airports, their roads, their vehicles—that is their civilization welcoming you. But as you spend time there, you hear the languages of these people, you taste their foods, you become aware of their thought process and their beliefs and religions, and that is where you partake of their culture.

What is more important for me to talk about here is about culture.

I don’t see culture as a vague abstract. For me, culture is a living organism. You cannot see it, but it is living. It breathes just as the people living under its canopy do. In North India, the chanting of the verses on the Holy Ghats, the rattling of the bells in the monasteries, the influence of Arabian architecture, these are evocative of the culture prevailing there. When you come to the South, the tinkling of the anklets of the dancers, the perfume of the sandalwood outside the temples, the heavily adorned sarees on the women, that is the culture there.

While, in a city like Mumbai, the culture would be an assimilation of all of these, because Mumbai is a city that is not homogenous. It is a microcosm of the several mini-cultures prevailing all over India, and even on foreign shores. That’s how the city has evolved. But even in Mumbai’s heterogeneity, there is a kind of uniformity that defines it. Even the foreigners who spend time in Mumbai have gradually become part of Mumbai’s culture. You cannot imagine walking for a few minutes on the South Mumbai streets, for instance, without spotting a foreigner. Or, for that matter, you cannot travel in a Mumbai local train without hearing at least six different dialects being spoken around you. That is Mumbai’s culture.

The problem today is that people are confusing these two.

They think that by changing the name of a city, they will change the city. They think that by changing the way people dress or talk or eat, they will change the people. They think that by censoring or changing the books and movies, they will change the thought process of the people.

But when has that ever happened? Have such cosmetic changes ever changed the core soul of the identity of a people?

Bombay changed to Mumbai in the nineties but ask any Mumbaikar—it makes no difference. We still think and live in the same manner as we used to think and live when it was Bombay. The changes that have happened are on account of the usual pace of progress; they haven’t come because of the change in our name. Who has the final laugh then?

We cannot change culture. History shows how heads of state have tried to change certain cultures. But even though they could destroy certain civilizations, they could not tame their cultures. They partially succeeded, that I won’t deny, but then the organism called culture continued to live and thrive and continued to give the society its identity, in some cases, even after its annihilation.

When someone tries to throw a stone in the lake of culture, there are ripples for sure. There is consent and dissent, and there is some transformation. But the core of the culture still stays.

What people also need to understand is that our culture will outlive all of us; it will outlive even our civilizations. Think of civilizations such as Pompeii or Mohenjo Daro. Their civilizations have long gone; but we still know a lot about how they were, which is because their culture still survives.

As a final thought—I’d like to say, culture does not come only from our bigger creative achievements. It’s not just the epics or the classics that define culture. Culture even comes from a single piece of wall art created by a student, or an ornament designed as a hobby by a woman at home, or an atrocious movie that was never watched, or a ridiculous book that was never read. All of it is our culture.

And the beauty of culture is that it doesn’t die. It evolves and it continues to thrive.

The writer Neil D’Silva is an author and screenwriter. He has six books to his credit and he writes for TV shows, digital shows, and films. He works primarily in the horror genre.

The writer Neil D’Silva is an author and screenwriter. He has six books to his credit and he writes for TV shows, digital shows, and films. He works primarily in the horror genre.

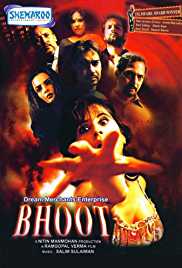

If you think I am giving the Ramsay movies too much weight here, think of the other horror director of India that met with success in the genre. Ram Gopal Verma in his early days. His horror movies, Raat, Vaastu Shastra, Phoonk, and Naina played on the psychology in a major way. In fact, even the insipid Bhoot was such a major success because for the first time an urban home was the setting of a mainstream horror film. And, I need to remind you of Kaun, of course. Though not technically horror, it is one of the scariest movies ever. That last pay-off, Urmila Matondkar’s dance of death on the terrace wall is something I will carry to my grave.

If you think I am giving the Ramsay movies too much weight here, think of the other horror director of India that met with success in the genre. Ram Gopal Verma in his early days. His horror movies, Raat, Vaastu Shastra, Phoonk, and Naina played on the psychology in a major way. In fact, even the insipid Bhoot was such a major success because for the first time an urban home was the setting of a mainstream horror film. And, I need to remind you of Kaun, of course. Though not technically horror, it is one of the scariest movies ever. That last pay-off, Urmila Matondkar’s dance of death on the terrace wall is something I will carry to my grave. Heard about this little nugget of an Indian horror film — Gehrayee? India’s answer to The Exorcist, and what an answer! It is a possession film at its core, but the movie spends a significant amount of time in the evolution of the girl and how it impacts the people around her. The actual frights come in much later in the movie. And again, what a pay-off!

Heard about this little nugget of an Indian horror film — Gehrayee? India’s answer to The Exorcist, and what an answer! It is a possession film at its core, but the movie spends a significant amount of time in the evolution of the girl and how it impacts the people around her. The actual frights come in much later in the movie. And again, what a pay-off!